A GRAMMAR OF NEW ITHKUIL

A CONSTRUCTED

LANGUAGE

3.0 BASIC MORPHOLOGY

In this chapter, we will discuss those morphological categories which are mandatory to a formative and which apply to both nominal and verbal formatives. In other words, those morphological slots from Sec. 2.3 above of a noun or verb which are grammatically required to be expressed by inflected affixes, rather than being optional. The specific categories we will discuss are Configuration, Affiliation, Perspective, Extension, Essence, Version, Function, and Context.

Standard Slot Structure of a Formative

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

|

|

(CC |

VV ) |

CR |

VR |

(CSVX...) |

CA |

(VXCS...) |

(VN

CN ) |

VC / VK |

[stress] |

|

|

Concatenation

status indicator |

Version |

Main Root |

Function +

Specification |

VXCS affix(es)

apply to stem but not to CA Form is -CSVX- (i.e.,

reversed from standard Slot VII VXCS

form) |

Configuration |

VXCS affixes

apply to stem + CA |

Valence

+ Mood/Case-Scope |

Case or Format or |

penultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VC ultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VK antepenultimate

stress = framed

Relation + VC |

|

|

consonantal

form consisting of either a glottal stop or a form beginning with -h-. |

vocalic affix |

cons. form |

vocalic affix |

consonant +

vowel |

if Slot V is

filled, CA is geminated |

vowel +

consonant |

Modular Slot

containing a |

vocalic affix

|

3.1 Configuration

To understand the concept of set relation and quantification of nouns

in New Ithkuil (i.e., what other languages term singular, plural, etc.) one

must analyze three separate but related grammatical categories termed Configuration,

Affiliation, and Perspective. These concepts are alien to other

languages. While they deal with semantic distinctions which are quantitative in

nature, these distinctions are usually made at the lexical level (i.e., via

word choice) in other languages, not at the morphological level as in New Ithkuil.

In this section we will deal first with Configuration, followed by Affiliation

in Section 3.2 and Perspective in Section 3.3.

Specifically, Configuration deals with the physical similarity or

relationship between members of a noun referent within groups, collections,

sets, assortments, arrangements, or contextual gestalts, as delineated by

internal composition, separability, compartmentalization, physical similarity

or componential structure. This is best explained and illustrated by means of

analogies to certain English sets of words.

Consider the English word ‘tree.’ In English, a single tree may stand

alone out of context, or it may be part of a group of trees. Such a group of

trees may simply be two or more trees considered as a plural category based on

mere number alone, e.g., two, three, or twenty trees. However, it is the nature

of trees to exist in more contextually relevant groupings than merely numerical

ones. For example, the trees may be of like species as in a ‘grove’ of trees.

The grouping may be an assortment of different kinds of trees as in a ‘forest’

or occur in patternless disarray such as a ‘jungle.’

As another example, we can examine the English word ‘person.’ While

persons may occur in simple numerical groupings such as ‘a (single) person’ or

‘three persons’ it is more common to find persons (i.e., people) referred to by

words which indicate various groupings such as ‘group,’ ‘gathering,’ ‘crowd,’

etc.

Segmentation and amalgamated componential structure are further

configurative principles which distinguish related words in English. The

relationships between car versus convoy, hanger versus rack,

chess piece versus chess set, sentry versus blockade,

piece of paper versus sheaf, girder versus (structural)

framework, and coin versus roll of coins all exemplify these

principles.

Another type of contextual grouping of nouns occurs in binary sets,

particularly in regard to body parts. These binary sets can comprise two

identical referents as in a pair of eyes, however they are more often

opposed or “mirror-image” (i.e., complementary) sets as in limbs, ears,

hands, wings, etc.

The semantic distinctions implied by the above examples as they relate

to varying assortments of trees or persons would be accomplished by inflecting

the word-stem for ‘tree’ or ‘person’ into one of twenty differnet configurations.

Additional semantic distinctions on the basis of purpose or function between

individual members of a set could then be made by means of Affiliation (see

Section 3.2 below) and by the use of specific affixes. For example, once the

words for ‘forest’ or ‘crowd’ were derived from ‘tree’ and ‘person’ via

Configuration, the words for ‘orchard,’ ‘copse,’ ‘team’ or ‘mob’ could easily

be derived via affiliation and affixes. (Such derivations into new words using affixes

are explored in detail in Chapter

7: Affixes.)

The category of Configuration consists of the amalgamation of three

separate factors: Plexity, Separability,

and Similarity.

·

Plexity is a three-way distinction as to whether an entity/event/act/state is

single or internally unified, is binary or two-halved in nature, or has three

or more components/pieces/parts/members.

These three states of Plexity are termed uniplex, duplex,

and multiplex (abbreviated as U, D, and M) .

·

Separability is a three-way distinction as to whether a

group of entities when considered as a whole have individual members which are

physically separate from each other, connected to each other in some way

(whether physically or abstractly or metaphorically), or fused together (whether

physically or abstractly or metaphorically).

These three states of Separability are termed separate, connected,

and fused

(abbreviated as S, C, and F as the second letter following the Plexity abbreviation

letter). Note that Separability does not

apply to uniplex entities/events/acts/states.

·

Similarity is a three-way distinction as to whether a group of entities

considered as a whole have individual members which are physically similar to

each other, physically dissimilar to each other, or which together constitute a

“fuzzy” category in terms of similarity (where the degree of similarity between

individual members is subjective, unascertainable, irrelevant or not easily

definable). These three states of

Similarity are termed Similar, Dissimilar, and Fuzzy (abbreviated S, D, and F

as the third letter following the Plexity and Separability abbreviation

letters). Note that Similarity does not

apply to uniplex entities/events/acts/states.

Based on the above, there are a total of twenty configurations,

indicated via the CA consonantal

affix in Slot VI of the formative. Note

that in addition to showing Configuration, this CA affix also indicates the Affiliation, Perspective,

Extension and Essence of the stem. The

twenty configurations are shown below, each with its consonantal affix that

appears in Slot VI of the formative:

|

UPX |

uniplex |

— * |

|

DPX |

duplex |

s |

|

MSS |

multiplex/similar/separate |

t |

|

DSS |

duplex/similar/separate |

c |

|

MSC |

multiplex/similar/connected |

k |

|

DSC |

duplex/similar/connected |

ks |

|

MSF |

multiplex/similar/fused |

p |

|

DSF |

duplex/similar/fused |

ps |

|

MDS |

multiplex/dissimilar/separate |

ţ |

|

DDS |

duplex/dissimilar/separate |

ţs |

|

MDC |

multiplex/dissimilar/connected |

f |

|

DDC |

duplex/dissimilar/connected |

fs |

|

MDF |

multiplex/dissimilar/fused |

ç |

|

DDF |

duplex/dissimilar/fused |

š |

|

MFS |

multiplex/fuzzy/separate |

z |

|

DFS |

duplex/fuzzy/separate |

č |

|

MFC |

multiplex/fuzzy/connected |

ž |

|

DFC |

duplex/fuzzy/connected |

kš |

|

MFF |

multiplex/fuzzy/fused |

ẓ |

|

DFF |

duplex/fuzzy/fused |

pš |

* The uniplex is shown by the absence of any Configuration affix;

if all five CA affixes

have their “zero”/default values, the CA

form is -l-.

Note that a formative in DPX Configuration

alone indicates that it constitutes a pair, without overtly specifying the

similarity or separability between the two member-entities of the pair.

Examples of Various

Configurations:

|

rrala ‘cat’-upx ‘a cat’ |

anzwul ‘spherical-shape’-obj-upx ‘a sphere’ |

|

|

rrasa ‘cat’-dpx ‘a pair of cats’ |

anzwut ‘spherical -shape’-obj-mss ‘a group of similar

spheres’ |

|

|

rraca ‘cat’-dss ‘a pair of similar

cats’ |

anzwuk ‘spherical-shape’-obj-msc |

|

|

rraţsa ‘cat’-dds ‘a pair of

dissimilar cats’ |

anzwup ‘spherical-shape’-obj-msf |

|

|

rrata ‘cat’-mss ‘a group of similar

cats’ |

anzwuf ‘spherical-shape’-obj-mdc |

|

|

rraţa ‘cat’-mds ‘a group of

dissimilar cats’ |

anzwuç ‘spherical-shape’-obj-mdf |

|

|

rraza ‘cat’-mfs |

anzwuž ‘spherical-shape’-obj-mfc |

|

|

Blöfêi onţlilu.

‘curved.translative.motion’-dyn/obj-mdc-asr/usp Stem.0-‘automobile’-sta/obj-ind ‘The driver drove

the car along a series of variously-sized curves.’ |

|

|

3.2 Affiliation

While the category of Configuration from the preceding section

distinguishes the relationships between the individual members of a set in

terms of physical similarities, physical connections, and number of

component-entities, the category of Affiliation operates to distinguish the

member relationships in terms of subjective purpose, function, or benefit.

Affiliation operates synergistically in conjunction with Configuration to

describe the total contextual relationship between the members of a set. Like Configuration,

the meanings of nouns or verbs in the various affiliations often involve

lexical changes when translated into English.

Returning to our earlier example of the word tree, we saw how a

group of trees of the same species becomes a grove in the MSC configuration. The word grove

implies that the trees have grown naturally, with no specific purpose or

function in regard to human design or utilization. On the other hand, groves of

trees may be planted by design, in which case they become an orchard. We

saw how trees occurring as a natural assortment of different kinds is termed a

forest. However, such assortments can become wholly chaotic, displaying

patternless disarray from the standpoint of subjective human design, thus

becoming a jungle.

As another example, we saw how the word person becomes group,

or gathering, both of which are neutral as to subjective purpose or

function. However, applying a sense of purposeful design generates words such

as team, while the absence of purpose results in crowd.

There are four affiliations: consolidative, associative, variative,

and coalescent.

Like Configuration, Affiliation is also indicated

as part of the CA affix-complex in Slot VI of the formative. An Affiliation affix constitutes the first

affix shown in the CA affix-complex in Slot VI, immediately

before the Configuration affix. The details of the four affiliations are

explained below along with their affixes.

|

3.2.1 |

CSL |

|

The Consolidative |

The consolidative affiliation is shown by a null affix, i.e.,

it is the absence of an Affiliation affix in slot VI that indicates consolidative

affiliation. This affiliation indicates

that the individual members of a configurational set are a naturally occurring

set where the function, state, purpose or benefit of individual members is

inapplicable, irrelevant, or if applicable, is shared. It differs from the associative

affiliation below in that the role of individual set members is not

subjectively defined by human design. Examples are tree branches, a grove, a

mound of rocks, some people, the clouds.

The consolidative is also the affiliation normally applied to

nouns in the uniplex

configuration when spoken of in a neutral way, since a noun in the uniplex specifies one single entity

without reference to a set, therefore the concept of “shared” function would be

inapplicable. Examples: a man, a door, a sensation of heat, a leaf. With

verbs, the consolidative would imply that the act, state, or event

is occurring naturally, or is neutral as to purpose or design.

Examples:

čveţa arsweţ zvata sřula

‘a bunch of tools’ ‘a group of

planets’ ‘a

set/group of similar dogs’ ‘a room’s function’

|

3.2.2 |

ASO |

|

The Associative |

The associative affiliation is shown by the Slot VI-initial

affix -l-, immediately followed by

the Configuration affix. Note that if

this affix is the only affix shown in the entire Slot VI CA

affix-complex, then it is instead shown by the stand-alone affix -nļ-. associative

affiliation indicates that the individual members of a configurational set

share the same subjective function, state, purpose or benefit. Its use can be

illustrated by taking the word for “soldier” in multiplex configuration and comparing its English

translations when inflected for the consolidative affiliation (= a

group of soldiers) versus the associative (= a troop, a

platoon). It is this consolidative versus associative

distinction, then, that would distinguish otherwise equivalent inflections of

the word for tree by translating them respectively as a grove versus an

orchard.

The associative

affiliation can also be used with nouns in the uniplex configuration

to signify a sense of unity amongst one’s characteristics, purposes, thoughts,

etc. For example, the word person inflected for the uniplex and associative

would translate as a single-minded person. Even nouns such as rock,

tree or work of art could be inflected this way, subjectively

translatable as a well-formed rock, a tree with integrity, a

“balanced” work of art.

With verbs, the associative signifies that the act,

state or event is by design or with specific purpose. The consolidative versus associative

distinction could be used, for example, with the verb turn in I

turned toward the window to indicate whether it was for no particular

reason or due to a desire to look outside.

čvelţa arswelţ zvalta sřunļa

‘a well-designed set of tools’ ‘an alliance of planets’ ‘a pack of similar dogs’ ‘the room’s singular

purpose’

|

3.2.3 |

COA |

|

The Coalescent |

The coalescent

affiliation is shown by the Slot VI-initial affix -r-, immediately followed by the Configuration affix. Note that if this affix is the only affix

shown in the entire Slot VI CA

affix-complex, then it is instead shown by the stand-alone affix -rļ-. The coalescent

affiliation indicates that the members of a configurational set share in a

complementary relationship with respect to their individual functions, states,

purposes, benefits, etc. This means that, while each member’s function is

distinct from those of other members, each serves in furtherance of some

greater unified role. For example, the word translating English toolset

would be the word for tool in the MDS (multiplex-dissimilar/separate) configuration (due to each tool’s

distinct physical appearance) and the coalescent

affiliation to indicate that each tool has a distinct but complementary

function in furtherance of enabling construction or repair activities. Another

example would be the word for finger inflected for the MSC (multiplex-similar-connected) configuration and the coalescent

affiliation, translatable as the fingers on one’s hand (note the use of the MSC configuration to imply the physical

connection between each finger via the hand). A further example would be using

the coalescent

with the word for (piece of) food to signify a well-balanced meal.

The coalescent naturally appears most often in conjunction

with the duplex configuration

since binary sets tend to be complementary. It is used, for example, to signify

symmetrical binary sets such as body parts, generally indicating a

lefthand/righthand mirror-image distinction, e.g., one’s ears, one’s hands,

a pair of wings. Pairs that do not normally distinguish such a

complementary distinction (e.g., one’s eyes) can nevertheless be

optionally placed in the coalescent

affiliation to emphasize bilateral symmetry (e.g., one’s left and right eye

functioning together).

With verbs, the coalescent signifies that related,

synergistic nature of the component acts, states, and events which make up a

greater holistic act, state, or event. It imposes a situational structure onto

an act, state, or event, where individual circumstances work together in

complementary fashion to comprise the total situation. It would be used, for

example, to distinguish the sentences He traveled in the Yukon from He

ventured in the Yukon, or I came up with a plan versus I

fashioned a plan.

čverţa arswerţ zvarta sřurļa

‘a toolset’ ‘a confederation of

planets’ ‘a dog team’ ‘a room whose

purposes are interrelated’

|

3.2.4 |

VAR |

|

The Variative |

The variative affiliation is shown by the Slot VI-initial

affix -ř-, immediately followed

by the Configuration affix. Note that if

this affix is the only affix shown in the entire Slot VI CA affix-complex, then it is instead shown by the stand-alone

affix -ň-. The variative

affiliation indicates that the individual members of a configurational set

differ as to subjective function, state, purpose or benefit. The differences

among members can be to varying degrees (i.e., constituting a fuzzy set in

regard to function, purpose, etc.) or at complete odds with one another,

although it should be noted that the variative

would not be used to signify opposed but complementary differences among set

members (see the coalescent affiliation below). It would thus be used to

signify a jumble of tools, odds-and-ends, a random gathering, a rag-tag

group, a dysfunctional couple, a cacophony of notes, of a mess of books, a

collection in disarray. It operates with nouns in the uniplex to render meanings such as a

man at odds with himself, an ill-formed rock, a chaotic piece of art, a

“lefthand-righthand” situation.

With verbs, the variative indicates an act, state,

or event that occurs for more than one reason or purpose, and that those

reasons or purposes are more or less unrelated. This sense can probably be

captured in English only through paraphrase, as in She bought the house for

various reasons or My being at the party served several purposes.

With non-uniplex configurations,

the use of the variative affiliation can describe rather complex

phenomena; for example, a sentence using the MSS configuration

such as The light is blinking in conjunction with the variative

would mean that each blink of the light signals something different than the

preceding or following blinks.

čveřţa arsweřţ zvařta sřuňa

‘a mish-mash of various tools’ ‘a disorganized group of planets’ ‘a

rag-tag group of dogs’ ‘a

room with disparate purposes’

3.3 Perspective

Perspective is the closest New

Ithkuil equivalent to the Number category of most natural languages (i.e.,

singular, plural, collective, etc.).

There are four perspectives: monadic, agglomerative,

nomic, and abstract,

shown respectively by the Slot VI affixes [null] (with stand-alone alternate of

-l),-r-, -w- (with

stand-alone alternate of -v), and -y- (with stand-alone alternate of -j).

The Perspective affix comes last in the sequence of affixes contained in

the Slot VI CA affix-complex.

The four perspectives are described below:

|

3.3.1 |

M |

|

The Monadic |

The monadic is unmarked

in terms of an affix (i.e., a null affix), unless it is the only affix in the

Slot VI CA affix-complex,

in which case its affix is -l-. It

signifies a single embodiment of a

particular configuration, meaning a contextual entity which, though possibly

numerous in membership or multifaceted in structure, or spread out through a

duration of time, is nevertheless being contextually viewed and considered as a

“monad,” a single, unified whole. This is important, since configurations other

than the uniplex technically

imply more than one discrete entity/instance being present or taking place. For

nouns, this corresponds to what in Western languages would usually be singular

number. For verbs, this can be thought of as a single

instance/occurrence/manifestation of an act, event, or state.

Thus, using the word tree for example, while there might be many

trees present in terms of number, the monadic

means they form only one embodiment of whatever particular Configuration

category is manifested. Using the MDC

configuration as an example, the monadic

would mean there is only one MDC

set of trees, i.e., one forest.

Singulative Equivalent: In natural

languages, nouns differ between those that can be counted and pluralized (e.g.,

one apple, four boys, several nations), and those which cannot be

counted or pluralized (e.g., water, sand, plastic, air, laughter). All

nouns are countable in New Ithkuil in that all nouns can exist as contextual

monads. As a result, monadic nouns in New Ithkuil which

refer to what are non-count nouns in other languages (or “collective” nouns

such as ‘leaves’ or ‘hair’) must be translated into what

linguists call the “singulative” mode, referring to the smallest salient single

manifestation of the entity in question, e.g., ‘a drop of water’, ‘a speck of dust’, ‘a single hair’, ‘a single leaf’,

‘a puff/whiff of air’, ‘a single

step/stride (of a walk/stroll)’, etc.,

whereas the more usual ways in which English and other languages express

manifestations of non-count nouns as vague amounts are expressed in New ithkuil

by the agglomerative perspective

in Sec. 3.3.2 below, e.g., ‘some water’,

‘some dust’, ‘(one’s) hair’, ‘some leaves’, ‘the air (here)’.

|

avsal ‘a season’ |

ţrala ‘a drop of water’ |

elzeţ ‘different rivers’ |

|

3.3.2 |

G |

|

The Agglomerative |

The agglomerative is marked by the affix -r- as the last (or only) affix in Slot VI. It indicates a neutral or fuzzy meaning in terms of number: ‘at least one X / one or more X / any number of X’. It is used when the specific number of an entity is irrelevant or the context of the utterance applies to either one or more than one of an entity. It also is used to create mass nouns from non-count nouns, as stated in the previous paragraph, e.g., ‘some rice / an amount of rice’, ‘(some) hair’, ‘(some / an amount of) water’, ‘the leaves’.

For verbs, the agglomerative distinguishes the same fuzzy “non-count” distinction as for nouns: ‘some X-ing occurs/manifests / there’s some X-ing going on’ versus monadic ‘a single instance of X occurs/manifests’.

NOTE: New Ithkuil does not have a Perspective corresponding to the plural ‘two or more’ meaning found in most Western languages. If needed, plural number can be conveyed by Degrees 5 or 6 of the XX2 affix (see the accompanying Affixes document).

|

avsar ‘one or more

seasons’ / ‘any number of seasons’ |

ţrara ‘some water’ |

elzeţra ‘at least one set

of different rivers’ |

|

3.3.3 |

N |

|

The Nomic |

The nomic is marked by the affix -w- in final position of Slot VI, unless it is the only affix in

Slot VI, in which case the affix is -v-. The nomic refers to a generic

collective entity or archetype, containing all members or instantiations of a

configurative set throughout space and time (or within a specified

spatio-temporal context). Since it is all members being spoken of, and no

individual members in particular, this category is mutually exclusive from the monadic

or agglomerative.

For nouns, the nomic corresponds approximately to the several constructions

used for referring to collective nouns in English, as seen in the sentences The

dog is a noble beast, Clowns are what children

love most, There is nothing like a tree.

With verbs, the nomic designates an action, event,

or situation which describes a general law of nature or a persistently true

condition or situation spoken of in general, without reference to a specific

instance or occurrence of the activity (it is, in fact, all possible instances

or occurrences that are being referred to). English has no specialized way of

expressing such generic statements, generally using the simple present tense.

Examples of usage would be The sun doesn't set on our planet, Mr. Okotele is

sickly, In winter it snows a lot, That girl sings well.

|

avsav ‘a season’ (as a generic concept) |

ţrava ‘water’ (as a generic concept) |

elzeţwa ‘different rivers’ (as a generic concept) |

|

3.3.4 |

A |

|

The Abstract |

The abstract is marked by the affix -y- in final position of

Slot VI, unless it is the only affix in Slot VI, in which case the affix is

-j-. Similar to the formation of English

abstract nouns using suffixes such as -hood or -ness, the abstract

transforms a configurative category into an abstract concept considered in a

non-spatial, timeless, numberless context. While only certain nouns in English

can be made into abstracts via suffixes, all Ithkuil nouns in all Configurative

categories can be made into abstracts, the translations of which must often be

periphrastic in nature, e.g., grove → the idea of being a grove

or “grovehood”; book → everything about books, having to

do with books, involvement with books.

With verbs, the abstract is used in verbal

constructions to create a temporal abstraction, where the temporal relationship

of the action, event, or state to the present is irrelevant or inapplicable,

similar to the way in which the English infinitive or gerund form (used as

substitutes for a verb phrase) do not convey a specific tense in the following

sentences: Singing

is not his strong suit; It makes no sense to worry about it;

I can't stand her pouting. As a result, the abstract

acts as a “timeless” verb form which, much like these English infinitives and

gerunds, operates in conjunction with a separate main verb in one of the other

three perspectives. The abstract is often used in

conjunction with certain moods of the verb (and Sec. 5.2) as well as the use of various “Modality”

affixes (see the accompanying Affixes document) which convey hypothetical or

unrealized situations, in which the temporal relationship to the present is

arbitrary, inapplicable, or unknowable.

|

avsaj ‘everything about a

season / ”season-hood”’ |

ţraja ‘everything having

to do with water’ |

elzeţya ‘different rivers

as an idea’ |

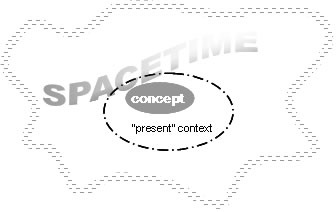

3.4 Extension

Extension is another morphological category for which there is no exact

equivalent in other languages. It applies to all formatives and indicates the

manner in which the noun or verb is being considered in terms of spatial or

temporal extent or boundaries. Another

way to put it is that Extension indicates what “part” of an

entity/act/event/state is being addressed or focused on. Extension is shown as part of a formative’s CA

affix in Slot VI which also indicates Configuration, Affiliation, Perspective

and Essence. There are six extensions: delimitive,

proximal,

inceptive,

attenuative,

graduative, and

depletive.

|

3.4.1 |

DEL |

|

The Delimitive |

|

The delimitive extension indicates that a noun is being

spoken of in its contextual entirety as a discrete entity with clear

spatio-temporal boundaries, with no emphasis on any particular portion, edge,

boundary, limit, or manifestation beyond the context at hand. It can be

considered the neutral or default view, e.g., a tree, a grove, a set of

books, an army. To illustrate a contextual example, the English sentence He

climbed the ladder would be translated with the word ladder in the

delimitive

to show it is being considered as a whole. With verbs, this extension

indicates that the act, state, or event is being considered in its entirety,

from beginning to end, e.g., She diets every winter (i.e., she starts

and finishes each diet). The delimitive can be thought of as an expanse of spacetime

that has definite beginning and ending points, beyond which the noun or verb

does not exist or occur. The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal

relationship of a concept in the delimitive to the context at-hand

(i.e., the spatio-temporal “present”).

|

|

|

The delimitive is shown by a null affix, i.e., it is the

absence of an Extension affix in the CA affix-complex that indicates delimitive extension. |

|

|

elzel ‘a river’ |

psulça ‘a situation’ |

uẓfäl ‘a tunnel’ |

erbräl ‘an explanation’ |

|

3.4.2 |

PRX |

|

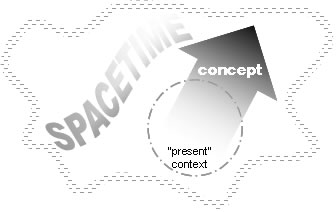

The Proximal |

|

The proximal extension indicates that a noun is being

spoken of not in its entirety, but rather only in terms of the portion,

duration, subset, or aspect which is relevant to the context at hand. It

would be used to translate the words tree, journey, and ladder

in the sentences That tree is hard there (e.g., in the spot where I

hit against it), She lost weight during her journey, or He climbed

on the ladder (i.e., it is not relevant to the context to know if he made

it all the way to the top). Note that in these sentences, the proximal does not

refer to a specific or delineated piece, part, or component of the tree or

ladder, but rather to the fact that delineated boundaries such as the ends of

the ladder or the entirety of the tree are not relevant or applicable to the

context at hand. With verbs, this extension signifies that it is not the

entirety of an act, state, or event which is being considered, but rather the

spatial extent or durational period of the act, state, or event relevant to

the context, e.g., She’s on a diet every winter (i.e., focus on

“having to live on” a diet, not the total time spent dieting from start to

finish). The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal relationship of

a noun or verbal concept in the proximal to the context at-hand

(i.e., the spatio-temporal “present”). |

|

|

The proximal is shown by the affix -t-, placed between the Configuration affix and the Perspective

affix in the CA

affix-complex. However, if the

Configuration affix is null (i.e., the Configuration of the word is uniplex),

then the proximal affix

is -d-. |

|

|

elzed ‘a section/stretch

of (a) river’ |

psulçta ‘the midst of a

situation’ |

ujrarft ‘an area/section of

a transportation system’ |

erbräd ‘a portion of an

explanation’ |

|

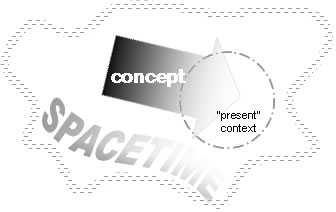

3.4.3 |

ICP |

|

The Inceptive |

|

The inceptive extension focuses on the closest boundary,

the beginning, initiation, or the immediately accessible portion of a noun or

verb, without focusing on the boundaries of the remainder. It would be used

in translating the nouns tunnel, song, desert, daybreak

and plan in the following sentences: We looked into (the mouth of)

the tunnel, He recognizes that song (i.e., from the first few notes),

They came upon (an expanse of) desert, Let’s wait for daybreak, I’m working

out a plan (i.e., that I just thought of). In verbal contexts it would

correspond to the English ‘to begin (to)…’ or ‘to start (to)…’ as in He

began reading, It’s starting to molt, She goes on a diet every winter, or He initiated a process of seduction. The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal relationship of a noun or verbal concept in the inceptive to the context at-hand (i.e., the spatio-temporal “present”). |

|

|

The inceptive is shown by the affix -k-, placed between the Configuration affix and the Perspective

affix in the CA affix-complex. However, if the Configuration affix is null

(i.e., the Configuration of the word is uniplex), then the inceptive affix is -g-. |

|

|

elzeg ‘the source of a

river’ |

psulçka ‘the beginning of a

situation’ |

ujrarfk ‘the initial part

of a transportation system’ |

erbräg ‘the start of an

explanation’ |

|

3.4.4 |

ATV |

|

The Attenuative |

|

The attenuative extension focuses on the end, termination,

last portion, or trailing boundary of a noun, without focusing on the

preceding or previously existing state of the noun. It would be used in

translating the words water, story, and arrival in the

sentences There’s no water (i.e., we ran out), I like the end of

that story, and We await your arrival. With verbs, it is

illustrated by the sentences It finished molting or She’s come off

her diet. The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal relationship of a noun or verbal concept in the attenuative to the context at-hand (i.e., the spatio-temporal “present”). The attenuative is shown by the affix -p-, placed between the Configuration affix and the Perspective

affix in the CA

affix-complex. However, if the Configuration

affix is null (i.e., the Configuration of the word is uniplex), then the attenuative affix is -b-. |

|

elzeb psulçpa ujrarfpa erbräb

‘the end of a river’ ‘a situation’s

end’ ‘end

of a transportation system’ ‘the end of an explanation’

|

3.4.5 |

GRA |

|

The Graduative |

|

The graduative extension focuses on a diffuse, extended

“fade-in” or gradual onset of a noun. It would be used in translating the

words darkness, wonder, and music in the following

sentences: Darkness came upon us, I felt a growing sense of wonder, The

music was very soft at first. With verbs it is illustrated by verbs and

phrases such as to fade in, to start gradually, to build up, and

similar notions, e.g., She’s been eating more and more lately. The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal relationship of a

noun in the graduative to the context at-hand (i.e., the

spatio-temporal “present”). The graduative is shown by the affix -g-, placed between the Configuration affix and the Perspective affix in the CA affix-complex. However, if the Configuration affix is null (i.e., the Configuration of the word is uniplex), then the graduative affix is -gz-. |

|

elzegz psulçga ujrarfga erbrägz

‘the headwaters of a river’ ‘an evolving situation’ ‘a developing

transportation system’ ‘a gradual explanation’

|

3.4.6 |

DPL |

|

The Depletive |

|

The depletive extension is the inverse of the graduative above, focusing on the

terminal boundary or “trailing” edge of a noun, where this terminus is

ill-defined, “diffuse” or extended to some degree, (i.e. the at-hand context

of the noun “peters out” or terminates gradually). Essentially, it applies to

any context involving actual or figurative fading. It would be used in

translating the words water, strength, and twilight in

the sentences He drank the last of the water, I have little strength left,

She disappeared into the twilight. With verbs, it is exemplified by the

phrases to wind down, to fade out, to disappear gradually and similar

notions, e.g., She’s eating less and less these days. The figure at right illustrates the spatio-temporal relationship of a noun or verbal concept in the depletive to the context at-hand (i.e., the spatio-temporal “present”). The depletive is shown by the affix -b-, placed between the Configuration affix and the Perspective affix in the CA affix-complex. However, if the Configuration affix is null (i.e., the Configuration of the word is uniplex), then the depletive affix is -bz-. |

|

elzebz psulçba ujrarfba erbräbz

‘the mouth of a river’ ‘last vestiges of a

situation’ ‘decline of a

transportation system’ ‘the unraveling of an explanation’

3.5 Essence

Essence refers to a two-fold morphological distinction which has no

counterpart in Western languages. It is best explained by reference to various

English language illustrations. Compare the following pairs of English

sentences:

|

1a) The boy ran

off to sea. 1b) The boy who

ran off to sea didn’t run off to sea. |

2a) The dog you saw is to be sold

tomorrow. 2b) The dog you saw doesn’t exist. |

Sentences (1a) and (2a) appear to be straightforward sentences in terms

of meaning and interpretation. However, at first blush, sentences (1b) and (2b)

appear nonsensical, and it is not until we consider specialized contexts for

these sentences that they make any sense. For example, (1b) would make sense if

being spoken by an author reporting a change of mind about the plot for a

story, while (2b) makes sense when spoken by a puzzled pet store owner in whose

window you earlier saw a dog that is no longer there.

Why sentences such as (1b) and (2b) can have possible real-world

meaning is because they in fact do not make reference to an actual boy or dog,

but rather to hypothetical representations of a real-world boy and dog, being

used as references back to those real-world counterparts from within an

“alternative mental space” created psychologically (and implied linguistically)

where events can be spoken about that are either unreal, as-yet-unrealized, or

alternative versions of what really takes place. This alternative mental space,

then, is essentially the psychological realm of both potential and imagination.

In Western languages, such an alternative mental space is implied by context or

indicated by certain lexical signals. One such group of lexical signals are the

so-called “modal” verbs of English, e.g., must, can, should, etc. as

seen in the following:

3) You must come home at once.

4) That girl can sing better than anybody.

5) We should attack at dawn.

Each of the above three sentences describe potential events, not actual

real-world happenings that are occurring or have occurred. For example, in

Sentence (3) no one has yet come home nor do we know whether coming home is

even possible, in Sentence (4) the girl may never sing a single note ever again

for all we know, and Sentence (5) gives us no information as to whether any

attack will actually occur.

3.5.1 NRM The Normal RPV The Representative

The morphological category of Essence explicitly distinguishes

real-world actualities from their alternative, imagined or potential

counterparts. The two essences are termed normal and representative, the

former being the default essence denoting real-world nouns and verbs, the

latter denoting alternative counterparts. By marking such counterparts

explicitly, a speaker can express any noun or verb as referring to a real-world

versus alternative manifestation, without having the listener infer such from

an explanatory context.

Essence is as part of the CA affix-complex which also

indicates Configuration, Affiliation and Perspective and Extension. normal essence is unmarked (i.e.,

it is the absence of any Essence affix that indicates normal essence. representative essence is shown by changing the value of the

Perspective affix at the end of the CA affix-complex: change the monadic affix from

null to -l-, unless all other CA

affixes are null, in which case change the monadic affix to the standalone

value of -tļ-; change the agglomerative affix

from -r- to -ř-; change the nomic affix from -w- to -m- unless immediately preceded by a consonant + t, a consonant + p, or a consonant + k,

in which case change the nomic affix to -h-; change the abstract affix from -y- to -n-, unless immediately preceded by a consonant + t, a consonant + p, or a consonant + k,

in which case change the nomic affix to -ç-.

|

Ẓalá kšili

ežḑatļëi. ‘see’-nrm ‘clown’-nrm-aff ‘ghost’-rpv-stm

‘The

clown sees what he thinks is/imagines to be ghost.’ |

Ẓatļá kšili

wežḑëi. ‘see’-rpv ‘clown’-nrm-aff ‘ghost’-nrm-stm ‘The clown imagines he is seeing a

ghost.’ |

As described in Sections 3.1

through 3.5 above, the CA affix-complex constitutes a single

agglutinative mass of consonant affixes conveying five different morphological

categories in a single morphological Slot (Slot VI). The initial consonant-form indicates

Affiliation, the second indicates Configuration, the third Extension, and the fourth indicates

both Perspective and Essence. These four

consonant-forms are strung together in sequential fashion to form the CA

complex as a whole. Note that all but

one of the four consonant-forms has a default form of zero, meaning that in

most cases, the CA complex will manifest fewer than four

consonant-forms. In fact, the most

commonly occurring CA form is CSL/UPX/DEL/M/NRM shown simply

by the lone affix -l-.

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

|

|

(CC |

VV ) |

CR |

VR |

(CSVX...) |

CA |

(VXCS...) |

(VN

CN ) |

VC / VK |

[stress] |

|

|

Concatenation

status indicator |

Version |

Main Root |

Function +

Specification |

VXCS affix(es)

apply to stem but not to CA Form is -CSVX- (i.e.,

reversed from standard Slot VII VXCS

form) |

Configuration |

VXCS affixes

apply to stem + CA |

Valence

+ Mood/Case-Scope |

Case or Format or |

penultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VC ultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VK antepenultimate

stress = framed

Relation + VC |

|

|

consonantal

form consisting of either a glottal stop or a form beginning with -h-. |

vocalic affix |

cons. form |

vocalic affix |

consonant +

vowel |

if Slot V is

filled, CA is geminated |

vowel +

consonant |

Modular Slot

containing a |

vocalic affix

|

Due to the agglutinative nature of the

CA affix-complex, it is helpful to illustrate its

phonological structure of in table form, as shown below. Note that, due to the

large number of consonant combinations that can exist within this

affix-complex, it is inevitable that certain consonant combinations will either

be difficult to pronounce, give rise to ambiguities with other affix

combinations, or even violate the phonotactic rules of the language. For these reasons, there are 19 consonantal CA

combinations that must be replaced by different consonant combinations. These replacement combinations are known as allomorphic substitutions and are

listed within the table below. (Note

that within the listing of allomorphic substitutions, the symbol [C] means “any

consonant”.)

CA

complex — Affiliation + Configuration + Extension + Perspective + Essence

|

AFFILIATION |

CONFIGURATION |

EXTENSION |

PERSPECTIVE

+ ESSENCE |

||||||||||

|

CSL |

consolidative |

— |

|

-DPX |

+DPX |

DEL |

delimitive |

— |

|

NRM |

RPV |

||

|

ASO |

associative |

l

(nļ) |

UPX |

uniplex |

— |

s |

PRX |

proximal |

t / d1 |

M |

monadic |

— (l) |

l (tļ) |

|

COA |

coalescent |

r

(rļ) |

M / D Duplex |

SS separate |

t |

c |

ICP |

inceptive |

k / g1 |

G |

agglomerative |

r |

ř |

|

VAR |

variative |

ř

(ň) |

SC connected |

k |

ks |

ATV |

attenuative |

p / b1 |

N |

nomic |

w (v) |

m / h2 |

|

|

Forms in parentheses |

SF fused |

p |

ps |

GRA |

graduative |

g / gz1 |

A |

abstract |

y (j) |

n / ç2 |

|||

|

M / D Duplex |

DS separate |

ţ |

ţs |

DPL |

depletive |

b / bz1 |

|

||||||

|

DC connected |

f |

fs |

Allomorphic Substitutions: pp → mp pb → mb rr → ns [C]gm

→ [C]x [C]bm →

[C]v tt→ nt kg → ng rř → nš [C]gn → [C]ň [C]bn → [C]ḑ kk →

nk çy → nd řr → ňs ngn → ňn fbm → (fv) →

vw ll → pļ řř → ňš [C]çx → [C]xw ţbn → (tḑ) → ḑy |

||||||||||

|

DF fused |

ç |

š |

|||||||||||

|

M / D Duplex |

FS separate |

z |

č |

||||||||||

|

FC connected |

ž |

kš |

|||||||||||

|

FF fused |

ẓ |

pš |

|||||||||||

1 Use the alternate form if the Configuration of the word is UPX

2 Use the alternate form when preceded by [C]t-, [C]k-, or [C]p-

3.6.1 Gemination of CA

when CSVX affixes are present in Slot V

If Slot V of a formative contains any affixes, it becomes necessary to show where Slot V ends and Slot VI begins. This is accomplished by gemination of the CA form as per the rules below. (This is why no Slot V/VII CS affix increment can be a geminated consonant.)

NOTE: When geminating a CA consonant-form, first apply all required allomorphic substitutions to the CA form as per the above table. Then apply the following rules:

1. For CA forms consisting of a single consonant, geminate the consonant, e.g., p → pp, t → tt, m → mm, c → cc, ẓ → ẓẓ, r → rr, s → ss.

2. The standalone form tļ becomes ttļ (although if it is in word-final position, it is actually pronounced tļļ as per the rule for gemination of affricates in Sec. 1.4).

3. For forms beginning with a stop (t, k, p, d, g, b) followed by a liquid or an approximant (l, r, ř, w, y), geminate the stop, e.g., . pl → ppl, gw → ggw.

4. For forms containing a sibilant fricative or affricate (s, š, z, ž, ç, c, č) in any position, geminate the sibilant fricative or affricate, e.g., kst → ksst, gz → gzz, çkl → ççkl, čtw → ččtw.

5. For forms beginning with either a non-sibilant fricative (f, ţ, v, ḑ) or a nasal (n, m, ň), geminate it unless previous rule No. 4 pertaining to sibilant fricatives (s, š, z, ž, ç) applies, e.g., fk → ffk, mpw → mmpw.

6. For forms beginning with a voiceless stop (t, k, p) followed by a fricative (s, š, f, ţ, ç), geminate the fricative, e.g., pf → pff, tçkl → tççkl, kst → ksst.

7. For CA forms ending in two stops, for which the previous six rules are inapplicable, use the following substitutions:

pt → bbḑ pk → bbv kt

→ ggḑ kp →

ggv tk

→ ḑvv tp

→ ddv

8. For CA forms ending in a stop (t, k, p, d, g, b) plus nasal (n, m, ň) for which the previous seven rules are inapplicable, use the following substitutions:

pm → vvm pn →

vvn km→xxm kn

→ xxn tm

→ ḑḑm tn

→ ḑḑn

bm → mmw bn → mml gm→ ňňw gn

→ ňňl dm

→ nnw dn → nnl

9. For forms beginning with l-, r- or ř-, apply one of the above eight rules as if the l-, r- or ř- were not present; if the resulting form including the initial l-, r- or ř- is not phonotactically permissible or is euphonically awkward, geminate the l-, r- or ř- instead.

Version

refers to a two-way distinction known in linguistics as “telicity”, i.e., whether

or not an entity, act, event, or state is goal- or result-oriented. Version addresses semantic distinctions which

are usually rendered by lexical differentiation (i.e., word choice) in

languages such as English. The two Versions are processual and completive,

as described below.

Standard Slot Structure of a Formative

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

|

|

(CC |

VV ) |

CR |

VR |

(CSVX...) |

CA |

(VXCS...) |

(VN

CN ) |

VC / VK |

[stress] |

|

|

Concatenation

status indicator |

Version |

Main Root |

Function +

Specification |

VXCS affix(es)

apply to stem but not to CA Form is -CSVX- (i.e.,

reversed from standard Slot VII VXCS

form) |

Configuration |

VXCS affixes

apply to stem + CA |

Valence

+ Mood/Case-Scope |

Case or Format or |

penultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VC ultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VK antepenultimate

stress = framed

Relation + VC |

|

|

consonantal

form consisting of either a glottal stop or a form beginning with -h-. |

vocalic affix |

cons. form |

vocalic affix |

consonant +

vowel |

if Slot V is

filled, CA is geminated |

vowel +

consonant |

Modular Slot

containing a |

vocalic affix

|

3.7.1 PRC The Processual

The processual

is the default version and is unmarked.

It describes all objects, entities, acts, conditions, or events which

are ends in themselves and not goal-oriented, i.e., are not focused on an

anticipated outcome or final purpose toward which a progressive effort is being

made.

3.7.2 CPT The Completive

The completive

version describes acts, conditions, or events which achieve, or are intended to

achieve, an anticipated outcome, i.e., which are oriented toward the

achievement of some purpose, outcome, or final state. Such a distinction is

usually handled by word choice in Western languages. The dynamism of Version

can be seen in the following comparisons:

|

PROCESSUAL

→ COMPLETIVE |

|

|

to hunt → to hunt down to

eat → eat all up |

to be pregnant → to give birth |

completive version is shown by modifying the Stem vowel-form in Slot II of the Formative. Change the Stem 1 vowel from -a- to -ä-. Change the Stem 2 Vowel from -e- to -i-. Change the Stem 3 vowel from -u- to -ü-. The Stem Zero vowel -o- changes to -ö-.

The following pair of sentences

illustrates the distinction between processual and completive version.

Arţtulawá

ulhiliolu wiosaḑca Iţkuil.

PRC-‘study’-dyn-rtr-obs Stem.3- ‘cousin’-obj-gen/1m-ind

Stem.2/n-[carrier]-clg1/1-thm

“Ithkuil”

‘My cousin studied the Ithkuil

language.’

Ärţtulawá

ulhiliolu wiosaḑca Iţkuil.

CPT-‘study’-dyn-rtr-obs Stem.3- ‘cousin’-obj-gen/1m-ind

Stem.2/n-[carrier]-clg1/1-thm

“Ithkuil”

‘My cousin learned the Ithkuil

language.’

Function refers to a two-way distinction as to whether the meaning of a formative refers to a static existential or psychological state, or a dynamic action or event. The distinction between STATIVE vs. DYNAMIC function is both objective and subjective. Certain contextual situations require one or the other, while for other contextual situations, either STATIVE or DYNAMIC Function can be used with each having a different meaning/interpretation.

Function is marked by the VR affix in Slot IV of the formative. Note that this VR affix is a triple-purposed affix; besides Function it also indicates one of four Specifications (see Sec. 2.4.4), as well as one of four Contexts (see Sec. 3.9). The full array of the 32 different VR affixes is shown in the table in Sec. 3.9.

Standard Slot Structure of a Formative

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

|

|

(CC |

VV ) |

CR |

VR |

(CSVX...) |

CA |

(VXCS...) |

(VN

CN ) |

VC / VK |

[stress] |

|

|

Concatenation

status indicator |

Version |

Main Root |

Function +

Specification |

VXCS affix(es)

apply to stem but not to CA Form is -CSVX- (i.e.,

reversed from standard Slot VII VXCS

form) |

Configuration |

VXCS affixes

apply to stem + CA |

Valence

+ Mood/Case-Scope |

Case or Format or |

penultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VC ultimate

stress = unframed

Relation + VK antepenultimate

stress = framed

Relation + VC |

|

|

consonantal

form consisting of either a glottal stop or a form beginning with -h-. |

vocalic affix |

cons. form |

vocalic affix |

consonant +

vowel |

if Slot V is

filled, CA is geminated |

vowel +

consonant |

Modular Slot

containing a |

vocalic affix

|

3.8.1 The Stative

As a general rule, stative function indicates that the formative refers to a static unchanging entity (at least within the duration of the contextual situation being referred to). The following would be marked for stative function:

· Nouns (i.e., formatives having VC case-marking in Slot IX) denoting physically tangible objects/entities being referred to only as a means of identifying them (i.e., any motion or change or usage being undergone by the object/entity is irrelevant to the speaker’s intent), e.g., a ball, a tree, a rock, a person, a cloud, etc.

· Nouns referring to collective, affective, intangible or abstract entities being referred to only as a means of identifying them (i.e., any change, motion or usage associated with the object/entity is irrelevant to the speaker’s intent), e.g., a crowd, a thought, an emotional state, a situation, a monarchical form of government, beauty as a concept, an aesthetic experience, an affective sensation, etc.

· Nouns referring to tangible actions/movements/motions/changes that the speaker is only referencing as a gestalt-like bounded entity (having an implied duration or spatial boundary) where the fact that the entity involves change/motion/movement/action/growth is irrelevant, e.g., (an instance/state of) laughter, (a pattern of) ocean waves, a conversation, (being out) fishing, (being out for) a walk, (an instance of) reading, (an instance/state of) hammering (going on), a meal [as an event, not a process], etc.

· Verbs (i.e., unframed formatives marked for VK Illocution/Expectation/Validation or framed formatives) which naturally refer to a non-dynamic unchanging state (at least within the duration/scope of the speaker’s intended context), including states of identification, denotation, description. Examples:

o She is a dancer; The sky is/appears orange; The sunset is beautiful; My name is Joe/I am called Joe; The box contains nails; You look terrible; I am reading; Money symbolizes evil; Unhappiness indicates failure; Disease is rampant in that city; Proper nutrition goes hand in hand with healthy children.

3.8.2 The Dynamic

As a general rule, dynamic function indicates that the formative refers to an action/movement/motion/change or a state involving change/motion/movement/action in which the change/motion/movement/action is relevant to the speaker’s intended meaning. For contexts in which a grammatical patient is involved (marked by inducive, affective, or absolutive case), the dynamic function implies a tangible effect/impact/change undergone by the patient as a result. the following would be marked for dynamic Function:

· Nouns referring to states involving change/motion/movement/action in which the change/motion/movement/action is relevant to the speaker’s intended meaning. Translations of such dynamic-marked nouns into English will often involve a gerund form or a paraphrastic form emphasizing the verbal derivation (in English) of such a noun. Examples: the (raging of the) storm; dancing; problem-solving; a meal [as a process], etc.

· Verbs involving change/motion/movement/action in which the change/motion/movement/action is relevant to the speaker’s intended meaning, especially those involving an agent/enabler and a patient.

Note that in many cases, a particular formative may take either stative or dynamic Function, resulting in subtly different meanings/translations as shown in the following examples. (Note that several of these examples contain the Slots IV and VI morpho-phonological “shortcuts” described in Sec. 3.10).

|

STATIVE |

DYNAMIC |

|

Byalá pa. ‘He has/shows/is showing

common sense.’ |

Byulá pa. (Byulá pu.*) ‘He uses/exercises/is

demonstrating common sense.’ [*if

emphasizing the resulting beneficial change in state] |

|

Vvralá mi

wurçpi. ‘Her passion is dance /

She feels passionate about dance.’ |

Vvralá mi

urçpuli. ‘Her passion is dancing /

She feels passionate about dancing.’ |

|

Tlasatřá çkava. Disease is rampant there. |

Tlusatřá çkava. Disease runs rampant

there. |

|

Txasá ku. They are having a meal. |

Txusá ku. They are eating a meal. |

|

Waltlá wele

lo. I make the child wear a

jacket. |

Altlúl wele

lo. I put a jacket on the child / I dress the

child in a jacket. |

|

Malá welu

wiosaḑcä espanya. The child is speaking (in)

Spanish. |

Mulá welu wiosaḑcä espanya. The child is saying

something in Spanish.* [*This

meaning can also be conveyed by using CTE Specification: mülá] |

|

Yeg arrlalu. The cheetah is running. |

Egúd arrlalu. The cheetah is running. |

Context is another morphological category with no equivalent in other

languages. It indicates what tangible or intangible features or aspects of a

formative are being psychologically implied in any given utterance. There is no

way to show this in translation other than by paraphrase. There are four

contexts: the existential, the functional, the representational,

and the amalgamative, explained in Sections 3.9.1 through 3.9.4 below.

Context is shown by modification of the Slot II Vowel-form. This is the vowel-form that also indicates

Specification (see Sec. 2.4.4) and Function (see Sec. 3.8). The vowel-forms for all three of these

morphological categories are shown in the table below.

Slot IV VR values

|

Function

|

Specification |

Context |

* For the four RPS forms beginning with -i-, the alternate forms shown are used when immediately preceded by -y-;

For the four RPS forms beginning with -u-, the alternate

forms shown are used when immediately preceded by -w- |

|||

|

EXS |

FNC |

RPS * |

AMG |

|||

|

STA |

BSC |

a |

ai |

ia / uä |

ao |

|

|

CTE |

ä |

au |

ie / uë |

aö |

||

|

CSV |

e |

ei |

io / üä |

eo |

||

|

OBJ |

i |

eu |

iö / üë |

eö |

||

|

DYN |

BSC |

u |

ui |

ua / iä |

oa |

|

|

CTE |

ü |

iu |

ue / ië |

öa |

||

|

CSV |

o |

oi |

uo / öä |

oe |

||

|

OBJ |

ö |

ou |

uö / öë |

öe |

||

3.9.1 EXS The

Existential

This existential is the default Context and focuses on those

features of a noun or verb which are ontologically objective, i.e., those that

exist irrespective of any observers, opinions, interpretations, beliefs or

attitudes. Similarly excluded from consideration in the existential is any

notion of a noun’s use, function, role or benefit. The existential serves

only to point out the mere existence of a noun as a tangible, objective entity

under discussion. It is thus used to offer mere identification of a noun or

verb.

For example, consider the sentence A cat ran past the doorway.

If the words corresponding to cat, run, and doorway are in

the existential, then the

sentence merely describes an objective scene. No implication is intended

concerning the subjective nature of the two entities or the action involved.

The sentence is merely stating that two entities currently have a certain

dynamic spatial relationship to each other; those two entities happen to be a

cat and a doorway, and the running merely conveys the nature of the spatial

relationship.

Frulawá warru přelu’a.

‘parallel.translative.motion’-dyn/exs-rtr-obs ‘cat’-sta/exs-ind ‘doorway’-sta/exs

-nav

‘The cat ran past the

doorway.’ [ = neutral description of physical scene

only]

3.9.2 FNC The

Functional

The functional context focuses on those features of a

formative that are defined socially by ideas, attitudes, beliefs, opinions,

convention, cultural status, use, function, benefit, etc. It serves to identify

not what a noun existentially is, but to show that the noun has specific (and

subjective) contextual meaning, relevance or purpose.

For example, in our previous sentence A cat ran past the doorway, if we now

place the cat, doorway, and act of running each into the functional, the ‘cat’

no longer simply identifies a participant, it makes its being a cat (as opposed

to say, a dog) significant, e.g., because the speaker may fear cats, or because

the cat could get into the room and ruin the furniture, or because cats are

associated with mystery, or because a neighbor has been looking for a lost cat,

etc. The ‘doorway’ now conveys its purpose as an entry, reinforcing what the

cat may do upon entering. Likewise, the verb ‘ran’ in the functional now

implies the furtive nature of the cat.

Fruilawá rrailu pře’ilua.

‘parallel.translative.motion’-dyn/fnc-rtr-obs ‘cat’-sta/fnc-ind ‘doorway’-sta/fnc

-nav

‘The cat ran past the

doorway.’ [ = focus on the personal or social

meaning/significance of the cat, the running past, and the doorway]

3.9.3 RPS The

Representational

The representational

context focuses on a formative as a symbol, metaphor, or metonym, in that it

indicates that the formative is serving as a representation or substitute for

some other concept or entity which is abstractly associated with it. For

example, the metaphorical connotations of the English sentence That

pinstripe-suited dog is checking out a kitty, can be equally conveyed in

Ithkuil by inflecting the words for ‘dog and ‘kitty’ into the representational

context. The representational is one of several ways that Ithkuil

overtly renders all metaphorical, symbolic, or metonymic usages (from a

grammatical standpoint).

Frualawá rrialu

při’olua.

‘parallel.translative.motion’-dyn/rps-rtr-obs ‘cat’-sta/rps-ind ‘doorway’-sta/rps

-nav

‘The cat ran past the doorway.’ [ = connotes

that the cat, the running past, and the doorway are metaphors]

3.9.4 AMG The

Amalgamative

The amalgamative context is the most abstract and difficult

to understand from a Western linguistic perspective. It focuses on the

systemic, holistic, gestalt-like, componential nature of a formative, implying

that its objective and subjective totality is derived synergistically from (or

as an emergent property of) the interrelationships between all of its parts,

not just in terms of a static momentary appraisal, but in consideration of the

entire developmental history of the noun and any interactions and relationships

it has (whether past, present or potential) within the larger context of the

world. Its use indicates the speaker is inviting the hearer to subjectively

consider all the subjective wonder, emotional nuances, psychological

ramifications and/or philosophical implications associated with the noun’s

existence, purpose, or function, as being a world unto itself, intrinsically

interconnected with the wider world beyond it on many levels.

Thus the amalgamative version of our sentence The cat ran past

the doorway would take on quite melodramatic implications, with the cat

being representative of everything about cats and all they stand for, the

doorway as being representative of the nature of doorways as portals of change,

thresholds of departure, and the juncture of past and the future, while the act

of running becomes representative of flight from enemies, rapidity of movement,

the body at maximum energy expenditure, etc.

Froalawá rraolu

přa’ölua.

‘parallel.translative.motion’-dyn/amg-rtr-obs ‘cat’-sta/amg-ind ‘doorway’-sta/amg

-nav

‘The cat ran past the doorway.’ [ = connotes a

focus on the emotional impact plus cultural significance of the event]

3.10 Restructuring of Slots I and II as a

“Short-Cut” for Slots IV and VI

In certain circumstances, it is possible to shorten the number of

syllables in a formative by eliminating the display of Slot IV and Slot VI and

instead showing their morphological information by means of Slots I and

II. Formatives containing this Slot

IV/VI elision are termed “short-cut” formatives. This is explained below.

Slot I of a formative carries a consonantal prefix, CC, that serves two functions: (1) to indicate whether the formative is a concatenated formative (explained in Chapter 8), and (2) to indicate whether certain VR+CA forms from Slots IV and VI have been elided (thus being instead indicated by the Slot I CC affix and Slot II VV affix).

The default value of Slot I is a glottal stop (’), which is unwritten in the language’s romanization scheme whenever in word-initial position. (Note that this means that no formative begins with a vowel-sound; any formative written with an initial vowel in the romanized writing system is to be pronounced with a preceding glottal-stop.) This unwritten glottal-stop signifies that (1) the formative is not concatenated (see Chapter 8), and (2) Slot II of the formative displays no Slot IV or VI information and Slots IV and VI of the formative have not been elided.

On the other hand, if Slot I contains either the value w- or the value y-, then this means that Slots IV and VI of the formative have been elided, and that Slot II, in addition to carrying its usual Stem + Version information for the formative, also conveys STA Function, BSC Specification, and EXS Context (i.e., the equivalent of a Slot IV VR affix value of -a-), as well as one of eight possible CA permutations from Slot VI, four of which are indicated by the Slot I value of w-, and four others by a Slot I value of y-. The specific CA values are indicated in the table below. (Note that all CA values are default CSL Affiliation, UPX Configuration, DEL Extension, M Perspective, and NRM Essence except as shown.)

Slot

II VV if Slot I CC is w-

or

y- (i.e., the formative

contains a Slot IV/VI a+CA shortcut)

|

Stem |

Version |

if CC = w then CA = [default] |

if CC = y then CA = PRX Extension |

if CC = w then CA= G Perspective |

if CC = y then CA = RPV Essence |

if CC = w then CA = N Perspective |

if CC = y then CA = A Perspective |

if CC = w then CA = G Perspective plus RPV Essence |

if CC = y then CA = PRX

Perspective

plus RPV Essence |

|

Stem 1 |

PRC |

a |

ai |

ia / uä |

ao |

||||

|

CPT |

ä |

au |

ie / uë |

aö |

|||||

|

Stem 2 |

PRC |

e |

ei |

io / üä |

eo |

||||

|

CPT |

i |

eu |

iö / üë |

eö |

|||||

|

Stem 3 |

PRC |

u |

ui |

ua / iä |

oa |

||||

|

CPT |

ü |

iu |

ue / ië |

öa |

|||||

|

Stem 0 |

PRC |

o |

oi |

uo / öä |

oe |

||||

|

CPT |

ö |

ou |

uö / öë |

öe |

|||||

The following

examples illustrate the distinction between using a Slot I/II shortcut and not

using one:

|

Yedpéi

mmoi. / Edpadéi

mmoi. ‘Where’s the thumping sound coming from?’ |

Weinţdâ.

/ Enţdarâ. ‘I recall at least one motorcyclist going by.’ |